The aesthetic significance of a plate of food is usually considered only for the few seconds it takes to bite into it. In fact, when taste and not style is of the essence, a bowl of grey-coloured slop could be just as satisfactory as a tower of carefully constructed haute cuisine, so long as said slop is well seasoned. In the age of culinary pretentiousness (ie now) with chefs like Heston Blumenthal producing food that has been tweaked, preened and garnished with the artistry of, well, an artist, it’s unsurprising that some of it should have found its way into an art gallery.

Tate Liverpool

Next weekend, a huge multi-level garden of exotic and colourful flowers, with visible roots dripping with soil and insects, and velvety blooms covered in flies and bugs, all made out of icing sugar, cake and marzipan, will form the centre piece at Cake Britain – the world’s first entirely edible art exhibition.

The show at London’s Future Gallery (which is appropriately sponsored Tate & Lyle Sugar), celebrates a nascent British art scene that uses jelly, cake, candy or other fare instead of paint or canvas. Dreamt up by a group who call themselves the Mad Artists Tea Party, and curated by cupcake-maker Lily Vanilli (also responsible for the edible garden), everything produced by artists and confectioners will be devoured within 72 hours of the exhibition opening.

It is not the first time food has been embraced by the art world. A scale model of an Algerian city made out of couscous by Kadia Attia was bought by Tate Modern in May. While wheat-coated semolina granules might be an unusual choice for a permanent installation (particularly as it goes flat as it perishes), Attia is only one of many creatives beginning to straddle the boundary between art and catering.

The “Jellymongers” aka Sam Bompas and Harry Parr, are famous for their elaborate jelly sculptures – notably a bright translucent copy of St Paul’s Cathedral that would have impressed its architect Christopher Wren. They’ve taken ideas from the 18th century about performance dining, with very original results. The pair recently made Occult Jam at the Barbican Gallery in July, as part of the Surreal House exhibition. They stewed jams using weird ingredients such as wood from Nelson’s ship the Victory and a speck of Princess Diana’s hair. For Cake Britain, the duo are planning “a doughnut-centric performance” with ideas from kitsch digital artist Jason Freeny.

Gloucestershire-based “food obsessed” artist, and maker of the world’s first chocolate room, Prudence Emma Staite, is another big British name involved in Cake Britain. During the election, she produced accurate pizza portraits of the party leaders out of dough, basil, mozzarella and pasata. She’s paired up with artist George Morton-Clark for Cake Britain, although details of their “marzipan and icing-sugar” creation are being kept strictly under wraps. Morton-Clark, whose paintings are rather morbid but use cartoonish colours (ideal for cupcakes), discussed a range of ideas with Staite. “She never came back to me to say, ‘Oh no, you can’t make that in cake’,” he says. “In fact, she thought of ways to make it bigger and better.”

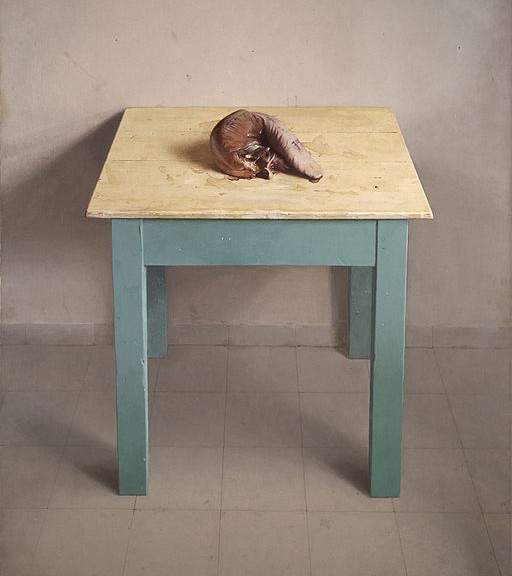

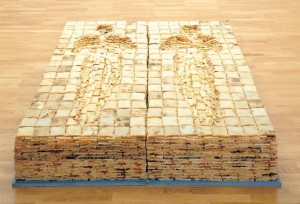

There is a pair of liquorice men’s brogues by Andy Yoder in Saatchi’s collection. And Antony Gormley’s Bed made from bread is currently on display at Tate Liverpool. Food is used by many artists because it is a useful and playful medium with which to represent something else. Choosing liquorice to make a pair of shoes, as in Yoder’s case, seems wonderfully appropriate as the dark, shiny confection is a stylised approximation of shoe leather. But Yoder, Attia and Gormley would most likely be appalled if someone viewing their work was to take a bite out of it. There is a stark dichotomy between artists who use food because it is an interesting material, and those for whom the eating of the art is simply the fulfilment of its purpose.

Staite, for example, wouldn’t be satisfied if people didn’t eat her work, which is designed to tantalise the taste buds as well as the eyes. “I really like seeing people eating the art,” she says. “It’s like a final journey. I often spend months making something and then it’s put on display and chomped up. Eating Obama’s face made out of cheese is just so much more interesting than having a normal block of cheddar.”

She’s trying to combat, what she calls the “ready meal culture,” by making bold statements with food to get people to consider its consumption more carefully. “The art is about putting the magic back into eating. So that when someone sees a life-size chocolate sofa they’ll think ‘wow, that’s amazing’. So that next time they eat chocolate, instead of just gorging on it and throwing away the wrapper, they’ll take a bit more time to think about their food.”

Bompas agrees that food art should be safe to consume, but says there is a fine line to tread when playing with the aesthetics of the edible as sometimes it can just be really bad taste (no pun intended) mucking about with food. He says: “Where do you find most food that looks like other stuff? At the low end: chocolate willies for hen parties, teddy-bear-shaped ham at Tesco etc. That’s why the element of skill is so important. If you get it wrong then it becomes really disgusting.”

Greta Ilieva

But playing with sensorial norms, and the added dimensions of taste and smell, can provide endless possibilities. Vanilli, who along with Alexander Turvey, is responsible for the edible garden at Cake Britain, recognises this. “The garden is going to be a little bit macabre, with beautiful flowers covered with insects and flies that you can eat. The idea being to play with perceptions, creating things that look repulsive but taste delicious,” she says. There is an element of performance and synaesthesia with such an approach. It aims to trick the viewer into a cerebral sense that what they’re looking at is inedible; meanwhile, their mouths are made to water by the sweet smells it gives off.

The fact that if the art goes uneaten it will go mouldy, lose its shape, attract flies, and end up as a stinking mass of nothing, is part of its draw. The intransigence is vital because if one didn’t eat it and enjoy it then all its beauty would be lost anyway – or the food (like Gormley’s bread, which was soaked in paraffin) will need to be treated with something to fix its appearance in time, making it inedible.

Eating art is satisfactory because it uses taste, touch and smell as well as being a visual feast. Eighteenth-century exponent of haute cuisine, Antoine “King of Chefs” Carême, famously remarked: “There are five fine arts – sculpture, painting, poetry, music and architecture – and the confectioner is the only artist to have mastered four of the five.” Just add to that a willingness to watch your mastery chewed up and swallowed by the ravenous hordes, and you have all the ingredients necessary for a food artist. Perhaps something of Blumenthal’s will make it into the Tate Modern next.

Cake Britain, Future Gallery, London WC2 (020 3301 4727) 27 to 29 August